As India continues to grapple with its growing dependence on imported edible oils, voices from within the country’s top policy-making body are calling for a renewed, practical approach to the problem—one that balances innovation with regulation, and ambition with caution. In a recent interaction, Ramesh Chand, member of the NITI Aayog and a senior agricultural economist, emphasized that India must embrace newer technologies, including genetically modified (GM) varieties of oilseeds, to truly move towards self-sufficiency. But such a move, he insists, must be paired with clear safeguards, especially in the form of robust labelling mechanisms that respect consumer choices.

Chand’s comments come at a time when the debate around genetically modified crops, particularly GM mustard, is again under legal scrutiny. As the Supreme Court deliberates on petitions concerning the environment ministry’s approval of GM mustard for commercial cultivation, Chand’s position adds weight to a nuanced national conversation—one that is as much about food security as it is about trust in science and regulation.

Productivity Stagnation and a Shrinking Path to Expansion

Chand made a case for why India, the world’s largest importer of edible oils, must consider alternate routes beyond just expanding cultivated land. “We cannot increase production by expanding the area under cultivation because that has limitations. Ultimately, it will have to be the productivity route,” he said.

He pointed to soybean as an example. While India’s yield has remained nearly flat for the past five decades, the United States has achieved a nearly 300% increase in productivity during the same period—largely by adopting GM technology. “If we use GM in soybean, our yield can immediately double or increase by 70-80%. If we use it with required caution, I don’t see any risks,” Chand noted, referencing the long-term use of GM crops in countries like the US, which have reported no adverse effects.

He also cited China’s recent move to approve 75 varieties of GM crops after years of hesitation as a signal that India cannot afford to remain on the sidelines any longer.

Trade Windows and Consumer Sensitivities

Chand suggested that this shift towards GM technology could also open doors for strategic trade relationships, particularly with the United States. He proposed that India could consider joint ventures such as importing oil from US-crushed soybeans or exporting de-oiled cakes after domestic extraction. However, he emphasized the need for stringent consumer labelling laws to ensure transparency and give consumers the right to choose.

“This is one area which we can offer to the US,” he said. “We have to be imaginative. This opens a window for us.” The approach, he said, could accommodate public sentiment while also laying the groundwork for practical trade arrangements.

Policy Shifts and the Roadblocks Ahead

Despite past setbacks in implementing farm sector reforms, Chand still believes they hold the key to unlocking agricultural potential. Although the central government had to roll back its earlier reform efforts in the face of widespread protests, he stated, “The future of agriculture lies in these reforms and increasingly involving the private sector.”

According to Chand, states that have not embraced these reforms continue to see stagnation in agricultural productivity. He stressed that although the Centre may not make another push for sweeping changes, some states have been issued advisory guidelines modeled on the earlier reforms. He pointed out that meaningful change will require state-level commitment and innovation.

He also underlined that the agriculture sector has shown commendable progress over the last decade. “It is for the first time in the history of this country that income growth in the farm sector has been at the same level as the non-farm sector,” Chand said, crediting the sector for contributing significantly to the overall economic momentum.

Also Read: Tiny Peptides, Big Possibilities: How CLE16 Could Help Crops Grow Without Chemical Fertilizers

A Reported Pathway to “Atmanirbharta” in Edible Oils

Earlier, at the Manthan event organized by Business Standard, Ramesh Chand had reiterated a key message that aligns closely with the NITI Aayog report—“Pathways and Strategies for Accelerating Growth in Edible Oils Towards the Goal of Atmanirbharta“ released back in August 2024, by Vice-Chairman Suman Bery, with Member Prof. Ramesh Chand and key representatives from the Ministry of Agriculture, ICAR, and industry. Presented by Dr. Neelam Patel, the report outlined a long-term roadmap to reduce India’s edible oil import dependence—central to the broader goal of self-reliance. To meet India’s growing edible oil demand options were limited—either to reduce consumption or rapidly adopts new agricultural technologies.

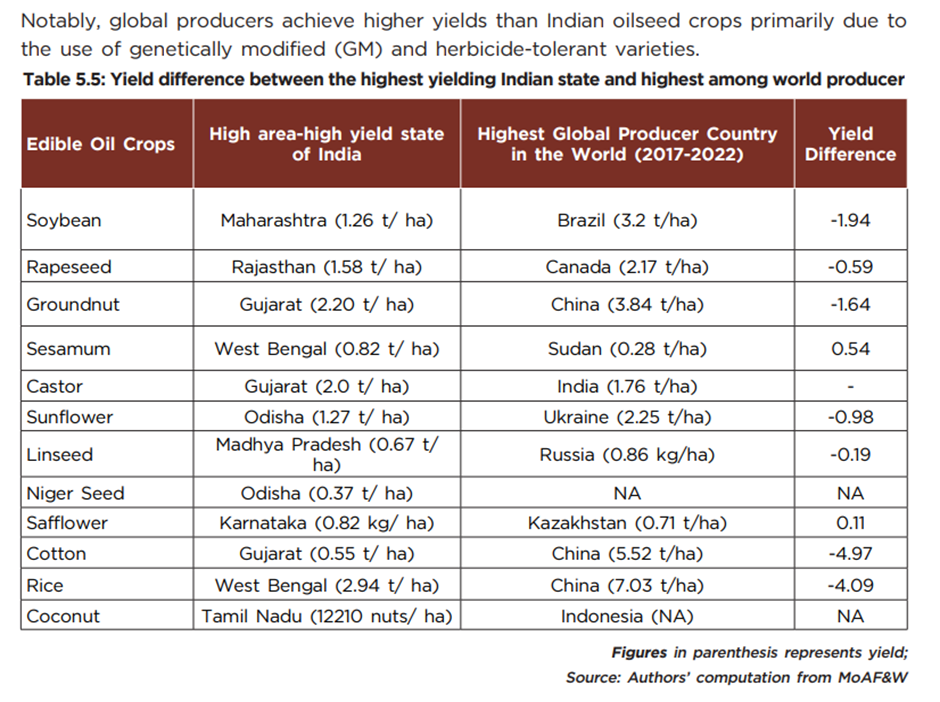

India’s per capita edible oil consumption reached 19.7 kg/year, driving imports to 16.5 million tonnes in 2022–23 and leaving domestic production to meet only 40–45% of demand. The report warned that without urgent intervention, the gap would widen further due to rising incomes and dietary changes. It also pointed to global producers achieving higher yields through GM and herbicide-tolerant varieties, suggesting India could close this gap by adopting improved seed technology, precision farming, and better crop management.

To boost productivity, prioritizing vertical expansion is essential. Countries like the United States, Brazil, and Argentina—leaders in soybean yields—offer valuable benchmarks. Their success stems from advanced seed technologies, precision farming, efficient irrigation, and integrated pest management, alongside the use of GM varieties. India can gain significantly by adapting these best practices to its own context. Even China, once cautious about genetically modified crops, has shifted its stance. The country has recently approved 75 GM varieties, signaling a broader global shift that India has so far been slow to respond to.

The report proposed a three-pronged strategy: crop retention and diversification, horizontal expansion using fallow and wastelands, and vertical expansion through yield improvements. A state-wise quadrant model was introduced to tailor interventions, with oil palm cultivation identified as a major opportunity—potentially adding over 34 MT of edible oil. Closing yield gaps in crops like sunflower and castor could also boost output significantly.

Looking forward, domestic edible oil production could rise to 36.2 MT by 2030 and 70.2 MT by 2047. Meeting even the most optimistic demand projections would require increasing the current 3% CAGR to 5.2%, supported by quality seeds, processing upgrades, PPPs, and R&D. Based on insights from 1,261 farmers across key states, the report laid a practical, data-backed path toward edible oil self-sufficiency, aligning food security with national economic priorities.

The report outlined the trajectory of edible oil consumption in India, which has reached an average of 19.7 kg per capita. Domestic production meets only 40–45% of the requirement, forcing the country to import as much as 16.5 million tonnes in 2022–23.

Through comprehensive modelling, the report projects multiple consumption scenarios up to 2047, estimating that India’s demand under current growth trends could outpace domestic supply by up to 40 million tonnes by 2047 in the worst-case scenario. This widening gap necessitates a multi-pronged approach involving horizontal and vertical expansion, technology adoption, better seed utilization, and a stronger processing ecosystem.

The findings also emphasize the potential gains from bridging yield gaps in oilseeds like sunflower and castor through modern farming techniques and the use of high-quality seeds. According to the report, while improved seeds alone can boost yield by 15–20%, this can rise to 45% if combined with better overall input management.

Yet, India’s seed replacement ratio remains worryingly low, hovering between 25% and 62%, far below the 80–85% target needed for a meaningful impact.

Government’s Bold Policy Shift

In a bid to address price inflation and revive domestic oilseed production, the Government of India made a bold policy shift last year, raising import duties on crude vegetable oils from 5.5% to 27.5% in September 2024. This move, as Sudhakar Desai, President of the Indian Vegetable Oil Producers’ Association (IVPA), explains, “currently the average domestic mustard and soyabean prices are trading slightly below MSP and mustard harvest is around the corner. Since India imports close to 60% of edible oil requirements, global prices will have a direct impact on the retail prices.

Current global tariffs, global bio-diesel policies, upcoming monsoon, zero duty imports from SAFTA countries, etc. will be key drivers of the market in the short term.” However, the aftermath of this tariff change has led to ripple effects that extend far beyond the intended objectives—revealing vulnerabilities in India’s import channels, particularly under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA).

The Indian Vegetable Oil Producers’ Association (IVPA) has flagged a sharp spike in duty-free edible oil imports from Nepal—over 1.80 lakh metric tonnes in early 2025 alone—raising concerns over third-country oils being re-routed to exploit SAFTA’s zero-duty provisions. This, IVPA says, is distorting the domestic market, pushing oilseed prices below MSP, and weakening local processors despite the government’s push for self-sufficiency through higher import duties.

IVPA warns that these inflows risk undoing policy efforts like the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC), causing revenue losses and hurting long-term reforms. It has urged stricter enforcement of Rules of Origin, better trade monitoring, and alignment of regional agreements with national priorities like Atmanirbhar Bharat. With edible oils influencing inflation, IVPA stresses that market stability is an economic priority.

India’s Stance on GM – Balancing Priorities, Bridging Gaps Through Strategy

Even the report called for three broad interventions: crop retention and diversification, horizontal expansion into unused or underused land (like rice fallow areas), and vertical expansion through improved yields. Specifically, utilizing one-third of the country’s rice fallow lands could yield an additional 3.12 million tonnes of oilseeds, while targeted palm oil cultivation could produce up to 34.4 million tonnes of edible oil. Alongside seed improvement, the report calls for modernizing the largely small-scale and underutilized processing industry, which currently uses only about 30% of its refining capacity.

To date, India has officially approved only Bt cotton for commercial cultivation. The introduction of GM food crops remains controversial, as evident in the ongoing legal scrutiny. In April 2024, the Supreme Court began hearing petitions challenging the environment ministry’s approval for GM mustard cultivation. Earlier, in July 2023, the Court directed the government to formulate a national policy on genetically modified crops, highlighting the need for a structured and transparent approach.

This cautious legal and policy environment reflects the tension between scientific advancements and public sentiment. While the potential benefits of GM crops are acknowledged, concerns around long-term health impacts and biodiversity remain prevalent. Chand argued that these concerns can be mitigated through responsible usage, consistent monitoring, and, most importantly, clear labelling standards.

India’s Stance on GM – Balancing Priorities, Bridging Gaps Through Strategy

Even the report called for three broad interventions: crop retention and diversification, horizontal expansion into unused or underused land (like rice fallow areas), and vertical expansion through improved yields. Specifically, utilizing one-third of the country’s rice fallow lands could yield an additional 3.12 million tonnes of oilseeds, while targeted palm oil cultivation could produce up to 34.4 million tonnes of edible oil. Alongside seed improvement, the report calls for modernizing the largely small-scale and underutilized processing industry, which currently uses only about 30% of its refining capacity.

To date, India has officially approved only Bt cotton for commercial cultivation. The introduction of GM food crops remains controversial, as evident in the ongoing legal scrutiny. In April 2024, the Supreme Court began hearing petitions challenging the environment ministry’s approval for GM mustard cultivation. Earlier, in July 2023, the Court directed the government to formulate a national policy on genetically modified crops, highlighting the need for a structured and transparent approach.

This cautious legal and policy environment reflects the tension between scientific advancements and public sentiment. While the potential benefits of GM crops are acknowledged, concerns around long-term health impacts and biodiversity remain prevalent. Chand argued that these concerns can be mitigated through responsible usage, consistent monitoring, and, most importantly, clear labelling standards.

Toward a Sustainable Edible Oil Ecosystem

Beyond technology, Chand also spoke about the broader economic landscape of Indian agriculture. According to him, the past decade has seen a marked improvement in both output and farmer incomes. “It is for the first time in the history of this country that income growth in the farm sector has been at the same level as the non-farm sector,” he observed.

This shift, while significant, isn’t uniform. Some states and regions have benefitted more than others, often depending on their openness to policy reforms and private sector participation. Chand made it clear that reforms introduced by the Centre—although eventually rolled back—were a serious attempt to reshape agriculture. “There is no sense… neither is there good politics in attempting those again,” he noted, hinting at the political risks involved in top-down policy moves.

Nevertheless, he maintained that the future of Indian agriculture is intertwined with reform. States that have adopted progressive measures or encouraged private sector involvement have seen better outcomes. Meanwhile, areas that have resisted change continue to show signs of stagnation.

Pragmatism Over Polarisation

As the conversation on GM technology in food intensifies in India’s policy circles and courtrooms, Ramesh Chand’s statements serve as both a diagnosis and a direction. Chand’s comments signal a broader shift in the way agricultural policy discussions are evolving in India. The message is clear: to secure its food future and improve farmers’ livelihoods, India must be open to change, but that change must be carefully calibrated.

As Chand put it, “We have to be imaginative. This opens a window for us.” Whether India steps through that window—or chooses to wait—will likely shape the trajectory of its agriculture sector for years to come.

India’s quest for edible oil self-sufficiency is not just about productivity numbers or reducing imports—it is about ensuring food security, economic resilience, and informed consumer choice. The debate over genetically modified crops isn’t just about technology—it’s about economics, public policy, and consumer rights. It’s about whether India can strike a balance between progress and caution, between self-sufficiency and global cooperation.

The road ahead, as laid out by NITI Aayog’s recent report and Chand’s evolving position, points to a future that demands both agility and accountability. It calls for a country willing to embrace new tools without losing sight of the social compact it must uphold with its farmers and consumers alike.